The Warning Label

The legal system consistently discourages self-representation in criminal trials. The prevailing doctrine holds that any person who acts as their own attorney is inviting failure. This message is echoed by judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and even legal textbooks. The reasons are not difficult to understand. The criminal process is complex, fast-moving, and emotionally punishing. Without training, most individuals cannot navigate it successfully.

The statistics support this view. Most Pro Se defendants are convicted. They fail to meet procedural requirements, alienate judges, and perform poorly in front of juries. Many enter the courtroom with misplaced confidence and exit with a sentence far harsher than any plea deal would have required. This pattern is not a myth. It is a systemic reality.

Hiring a Lawyer Is Negotiating to Lose

Despite these truths, another reality deserves attention. While representing oneself is disastrous for most, hiring a lawyer is not always the solution it appears to be. Many criminal defense lawyers are trained not to fight but to negotiate. They manage their cases in bulk, seek predictable outcomes, and maintain cooperative relationships with prosecutors and judges. Their priority is often speed and stability, not client empowerment.

This structure means that a criminal defendant who hires a lawyer is often committing to a strategy of partial loss. The majority of criminal cases in the United States end in plea deals, not trials. This pattern is driven in part by the caseload of the courts and the pressure on defense attorneys to resolve matters quickly. Very few lawyers will encourage a client to take a case to trial unless the likelihood of success is unusually high.

This does not mean that lawyers act in bad faith. It means they operate within a system that rewards expedience and penalizes resistance. For most defendants, that system offers the best available protection. For a very small number, it represents an unacceptable compromise. Those individuals are not simply choosing to represent themselves. They are rejecting a negotiation they never agreed to.

What the Pro Se Litigator Gains

The Pro Se Litigator gains full control of legal narrative, courtroom strategy, and case presentation. That control includes the right to decide which arguments to make, which facts to emphasize, and which values to uphold. No intermediary stands between the defendant and the judge, jury, or record. The defendant speaks directly and bears the full weight of every word. For the right kind of person, this is not a burden. It is a necessity.

However, the Pro Se Litigator operates under immense pressure. The court expects conformity to procedure and disdains improvisation. The judge may be impatient. The prosecutor may become aggressive. The jury may be suspicious. The defendant must master courtroom decorum, procedural timing, evidentiary standards, and rhetorical performance. Any misstep may be costly. Any loss of composure may be fatal to the defense.

Low External Locus of Identity

For these reasons, it is correct to say that the vast majority of people should not attempt to serve as a Pro Se Litigator in a criminal case. Approximately 95 percent of criminal defendants will benefit more from representation than from self-advocacy. This group includes not only those unfamiliar with legal rules but also those who lack the emotional control and strategic discipline necessary for the courtroom environment.

However, five percent of people may have the opposite experience. These individuals are not simply better suited to Pro Se litigation. In some cases, they are more capable than any attorney available to them. For these people, self-representation is not only rational—it is preferable.

To understand why a few succeed where most fail, one must look beyond skill into temperament. The Pro Se Litigator is not merely informed, but internally anchored. The defining trait is a low external locus of identity. This individual does not rely on institutional approval, professional affirmation, or public reassurance to validate their position. That absence of need allows for clarity under pressure and resilience in the face of procedural hostility. Without it, even the best-prepared person will eventually defer, submit, or break.

Profile of the Pro Se-Capable

These rare individuals tend to share certain characteristics that make them uniquely capable of navigating adversarial legal proceedings. These traits are not necessarily taught in law schools or developed through formal training. Instead, they are forged through high-stress experience, self-directed learning, and repeated exposure to systems of pressure.

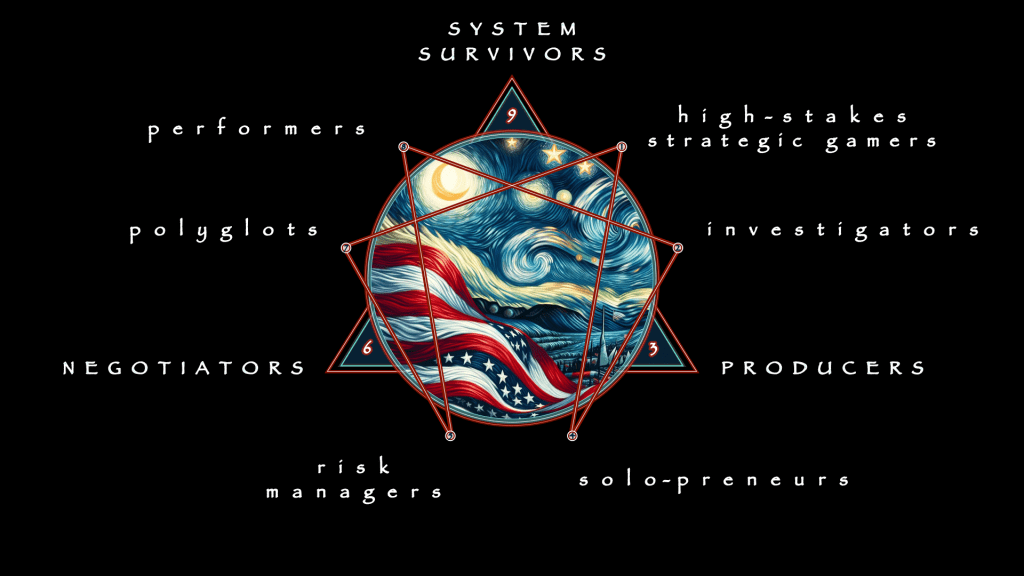

The following nine archetypes represent occupational or experiential profiles that signal potential fitness for Pro Se litigation:

- High-Stakes Strategic Gamers

These individuals are fluent in long-form competitive environments where bluffing, planning, and emotional detachment matter. They include chess players, poker professionals, Diplomacy players, and pool hustlers. Each of these activities builds stamina for ambiguity and tactical delay. - Investigators

These individuals collect, analyze, and deploy information under adversarial conditions. They may be investigative journalists, whistleblowers, OSINT researchers, or document analysts. They are comfortable building narratives from fragmented data and challenging institutional versions. - Producers

These are people who move resources through systems of resistance. They include union leaders, tenant organizers, and campaign managers. They also include many kinds of contractors. They all understand how bureaucracies work and how to shift outcomes through persistence and coordination. - Solo-preneurs

These people manage complex projects alone. They may be independent filmmakers, startup founders, or tactical organizers. Their key strength lies in executive function under strain and without support. - Risk Managers

These individuals thrive in uncertain, high-stakes environments where timing and decision quality are paramount. They may be emergency medical responders, military tacticians, or day traders. They have trained their minds to operate amid volatility and partial information. - Negotiators

These are people who resolve conflict without formal authority. They include community mediators, field organizers, and frontline crisis workers. They know how to listen, reframe, and pressure without escalation. - Polyglots

These people are fluent not just in languages but in linguistic systems. They are code-switchers, frame-adjusters, and context-aware communicators. Their “legalese” can rival that of any judge or DA when called upon. Their verbal flexibility often translates into rhetorical power in court. - Performers (Classical)

These individuals have trained in the techniques of vocal projection, emotional regulation, and spatial command. They include stage actors and voice-trained public speakers. They understand audience management and narrative pacing. - System Survivors

These individuals have lived within coercive institutions—prisons, hospitals, immigration systems—and learned how to resist, comply, and communicate under surveillance. They often include jailhouse litigants, asylum petitioners, and institutional staff with first-hand experience of procedural constraint.

Stacking as the Measure of Fitness

It is literally vital to clarify that none of these categories, by itself, is sufficient preparation to become a Pro Se Litigator. One or two traits may create confidence. Confidence is not nearly enough on this high-wire act. The courtroom penalizes error and rewards consistency. Only when an individual embodies three or more of these roles does a mere foundation for effective self-representation begin to coalesce.

An individual with four or five of these profiles operating in concert may be positioned to function not just adequately, but competitively. At that point, hiring a lawyer becomes less of a necessity and more of a convenience. It may save time. It may streamline filing. However, it no longer represents the most capable person in the room. The person best equipped to fight the case is already seated at the defense table.

Me, I humbly occupy seven seats . . . maybe eight, now.

Anyways, the more of these domains a person has internalized, the more fit they are to act as a Pro Se Litigator. This is not theoretical. It is tactical. Every additional layer of experience increases the ability to manage stress, recognize patterns, maintain narrative control, and perform within the narrow constraints of courtroom protocol.

Why Most People Should Not Attempt It

Despite the potential for exceptional performance, most people are not suited for this path. Representing oneself in a criminal case is not like writing a letter or making a speech. It is like playing three games of chess at once, while being shouted at, under surveillance, with your future at stake.

Most people do not perform well under those conditions. That is not a moral failing. It is a recognition of limits. The legal system is not designed to foster defendant development. It does not slow down to accommodate new learners. It does not offer time-outs or second chances. In that setting, instinct must already be trained. Composure must already be practiced. The voice must already know how to carry weight.

Most defendants are better served by competent legal counsel. That path offers insulation from technical error and emotional exhaustion. It also offers the chance to resolve the matter without enduring trial. These are real benefits, and they matter for most people most of the time.

Why Some People Must Attempt It

However, for the few who meet the criteria above, legal counsel may not be an enhancement. It may be a restriction. The lawyer may not understand the case. The lawyer may refuse to make critical arguments. The lawyer may misrepresent the defendant’s position. In some cases, the lawyer may actively undermine the defense in order to maintain rapport with the court or avoid reputational risk.

For a Pro Se Litigator with the required traits, these tradeoffs are not acceptable. The act of representation is not simply a tactical choice. It is a matter of identity, precision, and personal clarity. For that individual, self-representation is not a deviation. It is the only rational path forward.

Institutional Dependence as Control

This leads to a broader insight that extends beyond criminal law. Institutional dependence has become a general tool of social control. Systems increasingly demand not just obedience, but participation through approved intermediaries. In law, that intermediary is the lawyer. In medicine, it is the specialist. In education, it is the credentialed authority. The Pro Se Litigator challenges this structure.

By rejecting representation, the Pro Se Litigator denies the system its preferred method of containment. This act does not just assert individual agency. It tests the system’s ability to maintain legitimacy without procedural insulation. When that insulation is removed, the courtroom becomes what it always was: a managed conflict between unequal parties under selective rules.

The Pro Se Litigator enters that space not unarmed, but differently armed. The institution reacts not with celebration, but with resistance. This reaction reveals the truth. The system does not fear the fool who represents himself. The system fears the person who represents himself competently.

Closing Argument

The decision to go Pro Se is not made in court. It is made long before—through years of experience, practice, and internal development. The person who arrives capable did not train for one case. That person trained for a life of conflict with systems that do not recognize their authority unless forced. The trial is not the beginning. It is the continuation.

The courtroom is the only place in American life where speaking for yourself, without license or affiliation, is actively punished. That alone should disturb us. In every other arena—politics, art, religion—we celebrate those who speak in their own name. In court, we call it recklessness.

Perhaps this is because the courtroom is the last place where the state retains exclusive control over language and outcome. In that setting, an unmediated voice is not a glitch. It is a threat. A Pro Se Litigator who succeeds is not just a legal anomaly. That person is a breach in the firewall.

The real question may not be who is fit to go Pro Se. It may be why we have built a system where fitness is treated as defiance—where clarity, composure, and competence become disqualifying traits. The problem is not that people represent themselves poorly. The problem is that they must ask permission to speak in their own name.

Leave a comment