Speculation begins where investing and trading refuse to look—at the seams where policy frays and enforcement lags. Investors trust time; traders trust signals; Speculators trust neither. They operate in the space between decree and execution, where mispricing is born not from emotion but from design. The Speculator sees the rulebook as the trade and the state as the counterparty. Mastery requires learning to think like power—and move before it acts.

Speculation Is Statecraft In Reverse

Most people misunderstand what a Speculator is and what he does. They conflate speculation with gambling, mistaking disciplined reading for reckless chance. Or worse, they collapse it into manipulation, blaming Speculators for every price shock reported on the evening news. This confusion exposes not only economic illiteracy but also an unwillingness to confront the mechanics of coercion. Gambling depends on chance. Speculation depends on asymmetry.

The distinction becomes clearer when placed within a triangle of forces. At one corner stands the State, author of decrees and enforcer of compliance. At another lies Material Information, the factual substrate—public reports, private briefings, or concealed data—that shapes the field of possible trades. At the third wait the Speculators, whose craft begins only when the first two fall out of alignment. Investors build on stability, traders ride volatility, but Speculators interrogate enforcement itself. Their art is not prediction but orientation: watching for the second when the State declares more than it can execute, and when material facts undercut the authority of command.

Francis William Edmonds’ 1852 painting, The Speculator, captures this dynamic with domestic precision. A fashionable city broker unrolls deeds to “Rail Road Ave” before a rural couple seated by their hearth. His posture radiates confidence, yet their expressions reveal wariness. The paper in his hands is not mere information but leverage—an attempt to transform their ignorance of distant railroads into immediate obligation. The hearth, once a symbol of subsistence, becomes a theater of intrusion. Edmonds paints the moment as both comedy and warning: speculation is not random wager but the arrival of urban asymmetry in a frontier kitchen.

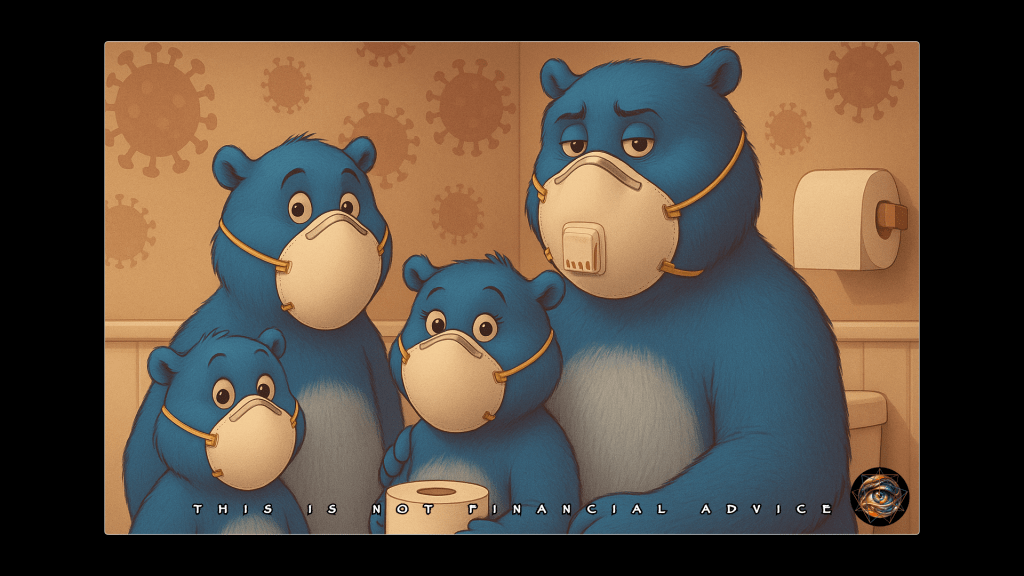

My modern parody thumbnail distills that composition into satire. Three corporate mascots crowd into a bathroom: one clutching a basket, one holding an endless roll, another masked against contagion. The paper here is not a deed but toilet tissue, rationed by panic and mispriced by rumor. The scene is absurd, yet it exposes the same dynamic Edmonds highlighted. Speculation remains an intrusion into ordinary life, only now the asset is not land along an iron track but Charmin missing from grocery aisles. It’s a Bear Market for the most basic of commodities.

Between the 1850s and the pandemic, the instruments changed but the theater did not. Then it was speculative deeds, in 2020 it was rationed rolls, but in each case the Speculator feeds on the lag between declaration and enforcement. The rural family doubted the railroad map because they could not see the tracks. The panicked shopper misjudged supply chains because no decree had constrained them. (Me, I installed a bidet.) Speculation begins not when people are afraid, but when power asserts itself faster than its machinery can follow.

The State cannot legislate in real time, which is a blessing. Every embargo, tax, or emergency order drags a tail of delay. Material information never arrives whole; it is fractured, partial, sometimes deliberately obscured. The Speculator orients at this intersection, timing the lag. His counterparty is not the crowd, nor chance, but the sovereign’s own timetable. The investor trusts in value. The trader trusts in signal. The Speculator trusts in neither, only in the inevitability that authority will overreach and information will escape its grip.

Thus, speculation is best understood as statecraft in reverse.

Where the State seeks to impose coherence, the Speculator measures the resulting fracture. Where Material Information offers certainty, the Speculator prizes the moment when it is mismatched with decree. What looks like opportunism from the outside is in fact disciplined orientation within this triangular arena. The theater may shift from kitchens to bathrooms, from deeds to tissue, but the play remains the same. Speculation is not a gamble on disorder. It is the art of timing order’s delay.

The Paper Trade Panic

When COVID first swept into the United States, opportunists scrambled to turn chaos into profit. Some filled garages with toilet paper and hand sanitizer, convinced that raw panic was itself a signal. They were wrong. Others moved N95 masks overseas before Washington could tighten customs controls. They were right. The difference was not cleverness or greed. It was orientation to power.

The toilet paper trade collapsed for a few reasons, but mostly because coercion never entered with force. Supply chains held, mills ran at capacity, and no authority restricted movement. Hoarders mistook hysteria for scarcity, and piled into garages what the state never claimed. When shelves refilled, their “speculation” rotted into liability. No motivated counterparty existed, because the sovereign had not acted. Worse, they relied on Amazon for distribution, which simply canceled them as an extension of public disgust with price gouging.

The mask trade was different. The state declared priority before it could enforce it. Agencies issued guidance, but customs and procurement lagged. Exporters exploited the gap, moving medical stock abroad while bureaucracy fumbled. Their profit came not from guessing demand but from reading delay. The counterparty was the sovereign itself—an authority that had spoken faster than it could move.

Speculation is not a gamble on panic or a forecast of crisis. It is a disciplined reading of coercion’s rhythm: when it asserts, how it lags, where its grip fails. Every new law, embargo, or bailout carries delay within it. The Speculator prices that delay like a barometric drop. Where governments seek to command, Speculators measure the space between order and obedience. Some merely shadow fear. Others interrogate authority. The sovereign may appear dominant, but every declaration opens a window.

That window, however brief, is the Speculator’s field.

Speculative Echelons

Speculators are not all alike, far from it. When you judge their practices by their results, correcting for their orientation (or access) to power, they arrange themselves along six progressively skillful plateaux. At the base, privilege substitutes for craft: proximity to the state delivers certainty disguised as acumen. One step higher, conviction is manufactured and sold, belief treated as tradable fuel. Beyond this lie the opportunists of rupture, who seize singular events, and the patient cultivators who farm crises as if they were seasonal harvests. Higher still operate the precision strikers, turning denial into spectacle by forcing institutions to stumble under pressure. At the summit stand the visionaries, whose designs outlive events, converting hidden strain into enduring indictment.

The spectrum measures not morality but distance: from those who co-opt privileged nonpublic information to those who foresee disorder by means of cognitive virtue alone. Each echelon reveals a different discipline of timing, a distinct way of extracting clarity from coercion, and a different legacy in the record of collapse. For each, I include notable exemplars and, for interactive ease, their names and thumbnails are also hyperlinked to extended POI reports.

Insider’s Insiders

Conviction is their currency. These figures do not refine information; they package belief, amplifying it until it circulates as value. A broadcast, a gesture, or a slogan substitutes for discipline, converting attention into momentum and audience into capital.

Accuracy is incidental. What matters is intensity, the self-fulfilling spread between what they assert and what others absorb. In this echelon, the operator resembles a performer more than a tactician. The market becomes a stage, speculation reduced to spectacle—a statecraft of persuasion rather than precision.

Nancy Pelosi illustrates how speculation can bypass craft entirely when proximity to state power substitutes for risk. Public records reveal a long trail of impeccably timed trades executed in her household accounts, often within days of key policy decisions. The trades themselves are administered by Paul Pelosi, her husband, a convenient arrangement that maintains the veneer of ethical separation. If the Speaker herself placed the orders, it would be an obvious violation; by outsourcing execution, the transactions remain technically permissible while politically radioactive. The pattern does not reflect superior analysis or tactical acumen. It reflects the privilege of foreknowledge, where market risk is erased by access to material information before it becomes public. Pelosi thus embodies the echelon of the Insider’s Insider: speculation reduced to access rather than insight, where advantage derives from corridors of power rather than discipline in the field.

Conviction Merchants

Conviction is their currency. These figures do not refine information; they package belief, amplifying it until it circulates as value. A broadcast, a gesture, or a slogan substitutes for discipline, converting attention into momentum and audience into capital.

Accuracy is incidental. What matters is intensity, the self-fulfilling spread between what they assert and what others absorb. In this echelon, the operator resembles a performer more than a tactician. The market becomes a stage, speculation reduced to spectacle—a statecraft of persuasion rather than precision.

Raoul Pal thrives not by consistently predicting markets but by converting conviction into a tradable asset. A former hedge fund manager, he reinvented himself as a media operator, building Real Vision into a platform where audience capture became as valuable as portfolio performance. His edge is not accuracy but amplification. When Pal issues a sweeping call—hyperinflation, crypto dominance, or the “exponential age”—the delivery is staged with such intensity that belief itself circulates as capital. His craft is persuasion, not position-sizing. The self-fulfilling cycle works as long as the audience accepts conviction as clarity, drawing new participants and prolonging momentum. In this echelon, speculation becomes spectacle: the market is secondary to the broadcast. Pal exemplifies how financial theater can be monetized, his stature resting less on realized trades than on his ability to transform narrative confidence into enduring liquidity.

Max Keiser operates as a showman whose trades are inseparable from his broadcast persona. A former Wall Street broker turned media provocateur, he transformed himself into a permanent megaphone for disruption, most famously as an early and relentless advocate of Bitcoin. His speculation is inseparable from performance: shouting price targets, staging public confrontations, and branding himself as a prophet of collapse. Accuracy is beside the point—his influence lies in mobilizing belief strong enough to pull capital along with it. Keiser thrives on spectacle, converting outrage and urgency into momentum that outpaces conventional analysis. His conviction is less a position than an instrument, traded across screens until it takes on the weight of inevitability. As an exemplar, he demonstrates the Conviction Merchant’s logic in its rawest form: speculation reduced to persuasion, profit drawn not from precision but from the willingness of others to buy the broadcast.

Event Specialists

Event specialists are creatures of singularity. Their craft crystallizes around one rupture, one trade, one decisive moment when distortion is most visible. They harvest volatility at its peak, entering history through the scale of capture rather than the repeatability of method.

Once the moment passes, the edge dulls. Without that scaffolding—whether a collapsing peg or a mortgage bubble swollen by fraud—the posture falters. These figures prove that fortune can arrive suddenly, but endurance requires more than proximity to disaster. They embody speculation as a one-time inversion of statecraft, not its sustained reversal.

John Paulson embodies the event-driven archetype through his legendary 2007 bet against subprime mortgage securities. His hedge fund structured credit default swaps that paid off spectacularly when the U.S. housing bubble imploded, generating billions in profit. Yet the brilliance of this strike also reveals the limits of the Event Specialist: it depended on a singular rupture, not a repeatable system. Paulson’s later funds failed to replicate this scale of success, underscoring how an Event Specialist’s fortune is often bound to the circumstances of one moment in history. He demonstrates how speculation can achieve historic visibility, but also how fragile that visibility becomes once the event passes.

George Soros achieved global notoriety in 1992 by “breaking the Bank of England,” shorting the pound sterling on the eve of its exit from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. This decisive strike netted him over a billion dollars and cemented his reputation as a master of singular rupture. Unlike Paulson, Soros leveraged this moment into a lasting platform, but the trade itself remains emblematic: one perfectly timed assault against a fragile peg. His later philanthropic empire overshadows the event, yet within speculation, Soros stands as the exemplar of how a single confrontation with sovereign policy can define an operator’s legacy. He remains the prototype of the Event Specialist: one who identifies a structural weakness, forces it open, and enters history through that fracture.

Crisis Farmers

Crisis farmers cultivate disorder as if it were seasonal. They wait through years of drawdown, seeding positions and tending imbalances until volatility ripens. For them, disruption is not anomaly but crop, a renewable yield extracted from the limits of suppression.

Patience is their weapon. When institutions exhaust themselves enforcing calm, these operators are already aligned with the rupture. They do not need to forecast the hour of collapse; they rely on the inevitability of recurrence. Their speculation mirrors statecraft in rhythm, harvesting the failures hidden inside its cycles.

Kyle Bass epitomizes the Crisis Farmer’s discipline by positioning for systemic unraveling long before others acknowledge its inevitability. His 2008 bet against subprime credit placed him in the ranks of event-driven legends, but his later posture reveals a different orientation. Bass has repeatedly staked capital on slow-burning macro imbalances—from Chinese banking fragility to sovereign debt unsustainability—treating crisis not as an anomaly but as a harvest that ripens on schedule. This patience distinguishes him from opportunists of rupture. His method accepts years of drawdown as the cost of waiting for enforcement failure. Bass demonstrates how speculation at this echelon is less about momentary brilliance and more about enduring alignment with systemic strain.

Greg Foss applies the logic of crisis farming to sovereign credit, treating government debt itself as a crop destined for default. His career in Canadian fixed income sharpened a conviction that fiat systems are inherently unstable, and his later advocacy of Bitcoin reflects this orientation. For Foss, each wave of debt monetization is not a temporary emergency but part of a recurring cycle that Speculators can cultivate. His framing of volatility as renewable resource illustrates the Crisis Farmer’s posture: patient, repetitive, and rooted in the certainty that suppression always carries its own expiry date. Foss exemplifies how speculation can outlast official reassurances by treating each policy fix not as repair but as seed for the next rupture.

Institutional Hitmen

Hitmen sharpen speculation into a weapon. They select contradictions too fragile to survive exposure and force them into daylight. A targeted strike—a short, a confrontation, a public dismantling—turns institutional denial into collapse. Their profit comes not only from the position but from the spectacle of authority stumbling.

Precision defines their method. They do not scatter capital; they fire it. Each move is both attack and demonstration, reshaping the field by proving that institutions are mortal. Their speculation is statecraft inverted—an act of destabilization aimed at credibility itself.

Mark Spitznagel represents the Institutional Hitman’s methodical precision. Through Universa Investments, he has built a reputation for targeted, asymmetric strikes against market denial. His specialty lies in tail-risk hedging—positions that appear costly during calm but deliver explosive returns when institutions stumble under stress. This discipline forces the system’s contradictions into daylight, transforming “insurance” into weapon. Spitznagel’s public philosophy, steeped in Austrian economics and warnings about central bank distortions, amplifies the theatrical side of his craft. Each crisis he survives not only validates his positions but undermines the credibility of the very institutions that promised stability. In him, speculation is sharpened into proof that power’s assurances are fragile and costly to maintain.

Hugh Hendry embodies the hitman’s flair for turning denial into spectacle. Known as “the acid capitalist,” he leveraged hedge fund positions with a provocateur’s tongue, confronting orthodoxy directly on media stages. Hendry thrived on contradiction, whether shorting housing before 2008 or publicly taunting central bankers about their blind spots. Unlike the patient farmer or detached cartographer, he weaponized visibility, forcing institutions to respond not only to market pressure but to ridicule. His trades were inseparable from his performance, each amplifying the other until the facade cracked. Hendry shows that the hitman’s strike is not merely financial but reputational—the moment when authority is made to bleed in public.

Collapse Cartographers

Cartographers draft collapse before it arrives. They inscribe patterns others dismiss, compressing hidden stress into diagrams that deny official reassurance. Their work is less prediction than authorship: a declaration that stability has already expired, rendered visible through form.

What endures is not the event but the drafter’s imprint. Long after headlines fade, their lines remain as indictment, proof that failure was legible in advance. To operate here is to stand furthest from power yet closest to its limits, translating disorder into lasting record. This is speculation as statecraft inverted completely—an authorship of collapse itself.

Martin Armstrong exemplifies the collapse cartographer: a figure who turns historical cycles into charts that outlive their moment. His Economic Confidence Model, built on the constant π and expressed in waves of 8.6 and 51.6 years, claims to map not just markets but civilizations. For Armstrong, capital flows are like tectonic pressure—silent until rupture, legible only to those who can read the stress.

Authority for him rests not on precise accuracy but on audacity. His Socrates AI system processes global data as if history itself were recursive, projecting turning points like his forecast of 2032 as a pivot for political order. Critics call it numerology, yet his endurance lies in offering diagrams of collapse before collapse occurs. The 2014 documentary The Forecaster elevated his model into spectacle, casting him as both savant and target of state reprisal.

Armstrong’s career, scarred by prosecution and 11 years in confinement, illustrates the danger of drawing maps that chart the sovereign’s fragility. His cartography is less prediction than indictment, a reminder that every empire carries its own expiration date in hidden arithmetic.

Doug Casey functions as the iconoclastic sovereign of the echelon model. His doctrine of Crisis Investing redefined speculation as the art of treating disorder as an asset class. In the late 1970s he argued that collapsing currencies, political upheavals, and resource shortages did not destroy markets—they created them. Where investors sought safety, Casey directed capital toward the distressed: precious metals, frontier equities, and emerging-market chaos. His method was not prediction but asymmetric preparation, balancing portfolios across “ten shots at tenfold” while accepting that most would fail. The thesis elevated crisis from hazard to opportunity, making volatility a field of calculated entry rather than avoidance.

Though remembered for libertarian polemics and fiction, Casey’s enduring significance lies in this reframing of panic as structure. He exemplifies the echelon that profits when institutions retreat, positioning speculation as statecraft inverted—timing the rhythm of collapse, and converting retreat itself into sovereign ground.

Every echelon, no matter how refined, confronts the same adversary: the sovereign intent on their erasure.

Individual operators can be outlawed, discredited, or crushed under regulatory weight. Trades can be banned, reputations ruined, lessons rewritten into cautionary tales. Yet the species of Speculator endures. Its survival is not cultural but structural.

They operate without a safety net, pricing fragility before it is permitted to surface. They do not chase movement, but anticipate the moment when the system can no longer perform stillness. The sovereign may succeed against individuals, but never against the function itself.

Wherever authority relies on coercion or corruption, Speculators arise to rebalance the distortion.

The High Ground Series

The High Ground novels by Doug Casey and John Hunt function less as entertainment than as a blueprint rendered in narrative form. The trilogy (so far) tracks the development of Charles Knight, a young contrarian who turns away from conventional careers to operate where state authority is weakest. Knight is not written as a hero in the conventional sense, nor as a tragic figure. He is designed as a proof-of-concept: a fictionalized operator testing the boundaries of Casey’s libertarian investment philosophy against settings of corruption, suppression, and systemic fatigue.

In Speculator, Knight enters the African mining frontier not to reform its dysfunction but to arbitrage it. Bureaucracy lags geology, and he inserts himself into that space. The novel frames speculation as tactical positioning in a jurisdiction where violence and fraud are as real as gold veins in the rock. Drug Lord brings Knight back to the United States, where he tests a compound that strips away self-deception. Here the speculative window is no longer geological but psychological, confronting the state’s monopoly over pharmaceuticals and the narratives that sustain prohibition. In Assassin, he emerges from prison into a fractured America, where masks, mobs, monetary failure and a populist “outsider” Presidential candidate signal a deeper confrontation with authority itself.

The High Ground series stops here, as an unresolved trilogy—half an edifice left unfinished, a framework without a conclusion.

Proposed as a six book arc, it may or may not be completed. What exists is less an academic narrative than a thriller about how resourceful individuals can operate when institutions consume their own credibility. Knight’s path does not describe destiny. It describes escalation under pressure, each stage a test of whether resistance must take sharper forms when softer ones fail.

Casey and Hunt’s fiction does not romanticize or even lament disruption. It treats corruption as baseline and statecraft as an opponent to be arbitraged, diverted, or neutralized. Knight moves not only with moral conviction but with structural clarity, exploiting lag wherever enforcement overreaches its capacity. His choices dramatize the spectrum described by the echelons: he begins as a crisis opportunist, becomes a farmer of dysfunction, and so on. The novels compress this progression, and they remain open-ended, their conclusion implied but as yet unwritten.

What gives the series its strange relevance is not just its philosophy but its timing. Written a year before COVID, Assassin depicts a United States where surgical masks and other face coverings become common. Knight uses them not as symbols of compliance but as tools to bypass facial recognition systems—a reminder that even the most advanced surveillance can be undone by a strip of fabric.

Fiction anticipated what enforcement would later co-opt. In the novel, masks frustrate the state; in the pandemic, the state imposed them. Knight’s masks were tools exploiting a weakness in state capacity. The real masks of 2020 became instruments of policy, their scarcity and enforcement opening and closing windows of profit. The passage from page to world was prescient, befitting a Speculator.

Charles Knight is not a hero, per se, but a protagonist as proof-of-concept.

The N95 Superhighway

The early pandemic offered two parallel stories that reveal the distance between opportunism and true speculation. Both began with scarcity, but only one understood how coercion bends markets. The toilet paper hoarders mistook panic for signal. They rushed to local stores, emptied shelves, and stacked their garages with bulky rolls of tissue, convinced that desperation alone would guarantee profit. For a few frantic weeks, some listed their stockpiles on Amazon or eBay, briefly commanding absurd markups. Yet the scheme collapsed almost as quickly as it began. Platforms shut down listings, governments issued warnings, and rations were imposed. The hustlers had mistaken a consumer reflex for a structural distortion. They had product but no pipeline, inventory but no insulation from enforcement.

The N95 mask profiteers worked differently. They operated like a decentralized enterprise, with family networks acting as both collection crews and distribution channels. Instead of waiting for online listings, they organized interstate sweeps. Buyers drove major highway corridors, hitting every hardware store, paint aisle, and supply depot along the way, emptying shelves one stop at a time. Gasoline costs were real, but spread across many participants. Coordination, not chance, created the harvest. The payoff came not from local resale but from exporting the masks to China, where black-market buyers were eager and restrictions weaker. A handful of families, not thousands of weekend hustlers, captured the profit because they combined logistics with network reach.

The contrast exposes what speculation demands. It is not enough to guess where scarcity will bite. One must have the means to move men as well as capital. The toilet paper trade was individualistic, small-scale, and dependent on consumer platforms that were easily shuttered by policy. The mask trade was collective, structured, and rooted in cross-border connections that outran enforcement. One was a hustle dressed as speculation. The other was speculation in its raw form—an enterprise organized to exploit the lag between state command and state control.

This difference in effort and structure also explains durability. The toilet paper hoarders relied on proximity: they bought what was close, stored what they could carry, and assumed demand would flow toward them. Their error lay in treating retail platforms as neutral “fences” for their booty, never realizing that Amazon and eBay functioned as extensions of state enforcement once public anger mounted. The N95 profiteers, by contrast, extended their reach. They created temporary labor forces, mapped corridors, and moved supply beyond the immediate field of regulation. Where one group placed faith in platforms, the other built a shadow distribution system.

Like traders and investors, Speculators do not produce anything. None of these occupations is like running a business, per se, since none creates any products or services for clients. Unlike traders and investors, however, Speculators are entrepreneurs, in that they organize time, networks, and opportunity more like producers than consumers. They harvest distortions without creating value in the conventional sense, and yet their operations demand skill, discipline, and risk management of a different order. The N95 families proved this by turning gasoline, coordination, and cross-border ties into a functioning pipeline.

Both episodes show that speculation lives in the gap between announcement and action.

Where coercion creates delay, profit appears. The toilet paper case also proves, however, that most who chase scarcity mistake emotion for structure. They overestimate their independence, underestimating how quickly platforms or regulators can erase their gains. The mask traders demonstrate the opposite: a few, properly organized, can turn delay into fortune by treating coercion itself as the commodity. They did not speculate on demand; they speculated on enforcement delay. Their profit was not proof of consumer panic but of bureaucratic lag.

These twin stories close the loop from our earlier examples. The toilet paper hoarders serve as the negative case: movement without structure, scarcity without signal. The mask exporters stand as the positive case: structure without legitimacy, signal without permission. Taken together, they show why speculation is more than timing—it is the discipline of orchestrating fragility before the state can reclaim it.

What Cannot Be Priced Will Be Proven

Speculators persist not because they are hidden but because they are integral. They operate in rhythm with authority, not against it—moving into the seam where legitimacy is declared faster than it can be enforced. What looks like breakdown is often choreography, or Natural Selection. Mispricing is not discovered in those moments; it is created, with the understanding that someone will stand ready to take it. The move is not to anticipate collapse, but to recognize how long failure can be monetized before it is admitted. Volatility is neither enemy nor accident. It is a release valve—measured, delayed, and priced into who may enter and who must exit.

Now, the field is open to more players than ever.

Genealogy no longer guards the gates. Public records, customs filings, and blockchain ledgers expose more distortion than any privileged memo once did. Material information has multiplied, and its signals, whether faint or obvious, circulate beyond the closed rooms where policy is drafted. Anyone attentive can see the delay. Few have the orientation to price it.

Speculation does not balance markets as a civic duty or extend credit to authority’s architecture. It simply exploits the contradiction between order asserted and order achieved. In that gap, fortune belongs to those who can distinguish between staged scarcity and enforced scarcity, between rumor as theater and regulation as choke point. To read this way is to shift vantage, not allegiance. Authority will always declare control; markets will always echo belief. Only time reveals whether enforcement has teeth.

The Speculator enters not with faith but with distance, measuring what cannot be concealed: that every system, no matter how rehearsed, lags behind its own command.

Leave a comment