Three Procedural Imperatives

A federal complaint under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 does not reach the merits because it is righteous. It survives because it is engineered. Most plaintiffs lose before any facts are heard—not due to the absence of a violation, but because they misunderstand what federal courts demand: jurisdiction, precision, and procedural obedience. The law recognizes constitutional wrongs only when they are pleaded through the correct filters. Those filters are standing, discovery access, and venue control. Each functions as a gate, and each gate is guarded.

Statistics confirm the terrain. In up to 90% of cases the Pro Se Litigator loses, not because his claims lack merit, but because he fails to meet the procedural thresholds that represented parties navigate with institutional knowledge. The uncounseled rate in federal civil cases hovers just above 10% overall, but in civil rights and employment discrimination actions, pro se rates climb to 1 in 4, or higher. These plaintiffs are not screened for the strength of their claims—they are screened for their ability to comply with federal procedure. When they fail, dismissal is swift, and the record never reflects whether a constitutional violation occurred. It reflects only that the plaintiff failed to plead one correctly.

No court considers your grievance unless you first prove Standing (0).

The doctrine does not test whether the government harmed you, but whether the court can act on your behalf without violating Article III limits. If you cannot show a specific personal injury, traceable to the defendant’s conduct, and fixable through the court’s authority, your case is dismissed before a single document is exchanged. Even if Standing (0) is established, Discovery (-) does not begin automatically. Courts permit the government to file a motion to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6) and simultaneously move to stay all Discovery (-). This tactic blocks you from obtaining the very records that would strengthen your claim. If your complaint does not survive dismissal, you will never see the evidence in the defendant’s possession.

Disabuse yourself of the belief that this is anything but standard operating practice.

No less vital, Venue (+) is not a formality, but a tactical position. Plaintiffs who file in the wrong district, or who fail to anchor Venue (+) with jurisdictional facts, invite transfer under 28 U.S.C. § 1404. States exploit this vulnerability to shift the case to districts where judges are more favorable to institutional defendants and/or more hostile to the Pro Se Litigator. If you do not control the ground, you do not control the terms.

Procedure is not the machinery behind the law. It is the law’s interface with power. Plaintiffs who ignore that fact are not denied justice, per se. Rather, they are removed from the field before the contest begins.

As an act of pro bono service, these imperatives will be explored as a series of Socratic questions. Although I write from experience, the particulars of my case(s) are immaterial to the strategic and tactical considerations in yours. Therefore, selection and arrangement follow a strict optimization rubric:

- Pressure-test a procedural failure point

- Identify a tactical opportunity, or

- Reveal a State countermove to be neutralized

No question will address merit, morality, or emotion. Instead, each tests for procedural fitness and strategic awareness. If you cannot answer all six cleanly, then you are walking into a trap.

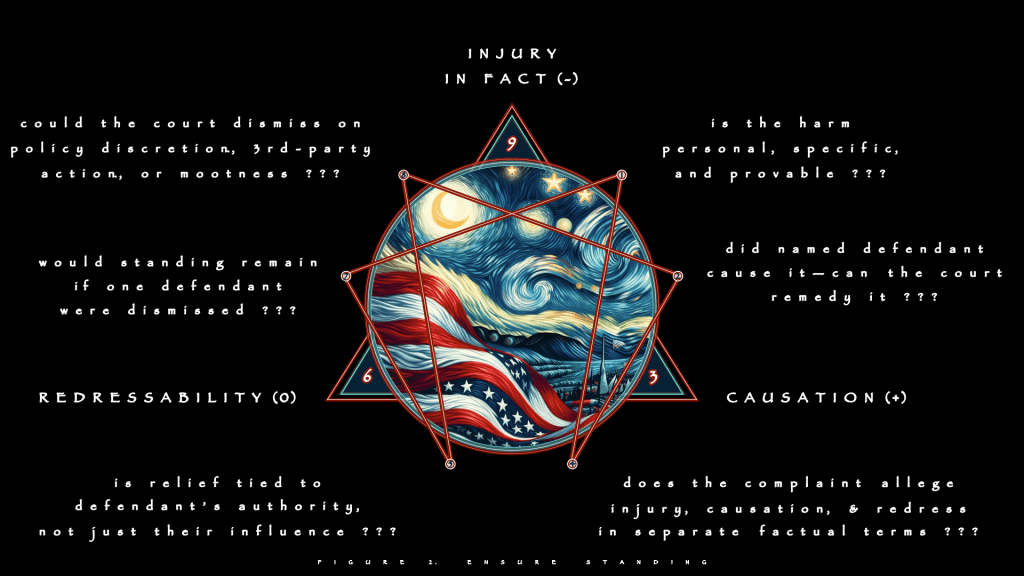

Ensure Your Standing

Federal standing doctrine originates in constitutional text, but its modern application is strategic filtration. Courts use standing to avoid addressing policy or controversy unless the plaintiff meets three criteria: actual injury, causal connection to the named defendant, and judicial redressability. Each of these terms has specific meaning, and each carries an embedded trap. Failure on any prong defeats jurisdiction. That defeat is final unless the complaint is amended correctly and resubmitted within the statute of limitations.

Have I identified a specific personal harm that is distinct from general public grievance, and can I support it with documentation or sworn facts?

An actual injury must be concrete and particularized. It cannot be hypothetical, general, or speculative. Courts demand that the plaintiff suffer harm that is personal, measurable, and specific. A vague allegation of “emotional distress” or “violation of civil rights” does not satisfy this requirement. A seizure of property, a denial of access, a lost job, a revoked license—these qualify, but only when detailed precisely in the pleadings. The plaintiff must describe what happened, when it happened, who caused it, and how it materially affected their interests. Without such detail, the court will not inquire further.

Can I draw a direct, fact-based line from the named defendant’s conduct to that harm, and does the remedy I’m seeking fall within the court’s power to grant?

Causation requires more than narrative. The plaintiff must connect the injury to the named defendant in a linear, defensible path. Federal courts do not recognize causation by implication, institutional influence, or atmospheric contribution. The harm must flow from a decision, action, or omission by the person or entity sued. If the injury came from a subordinate, but the complaint names a policymaker, the court will dismiss unless the plaintiff shows how the policy itself directly caused the act. This is not about blame. It is about structure. Legal causation must track control, not narrative resonance.

This becomes critical in § 1983 actions against municipalities. Under Monell v. Department of Social Services, a municipality cannot be held liable on a respondeat superior theory. The plaintiff must prove that the constitutional violation resulted from an official policy, custom, or practice, or from deliberate indifference in failing to train or supervise. This means identifying the policy in the complaint, connecting it to the specific harm suffered, and demonstrating that the policy was the moving force behind the injury. Without this structure, causation fails, and the case is dismissed regardless of what individual officers did.

Redressability is the final gate. The court must be able to order a remedy that would materially alter the plaintiff’s condition. This requires that the requested relief be both available and effective. If the harm cannot be reversed, or if the court lacks authority to bind the defendant, redressability fails. Plaintiffs often lose here because they name defendants who cannot implement the change requested. For example, one may sue a state licensing board over a denial but request relief that only the legislature can provide. The court will decline jurisdiction on that basis, regardless of the underlying harm.

The State exploits these elements with precision. Government attorneys are trained to identify gaps between the facts alleged and the procedural thresholds required. They will argue that your injury is not personal, that your harm was caused by someone else, or that your remedy is speculative. These arguments are often persuasive because most pro se complaints are drafted with moral logic, not jurisdictional architecture.

To defeat these moves, the plaintiff must write the complaint as if responding to a motion to dismiss before it is filed. This means building the standing elements into the factual section of the pleading, not merely asserting them in jurisdictional boilerplate. The facts should illustrate injury, causation, and redressability without reliance on legal conclusions. The complaint must do more than tell a story. It must establish the court’s authority to hear it.

Break the Rule 12(b)(6) Chokehold

Even when standing is secured, the real contest has not begun. The defense will often respond to the complaint with a Rule 12(b)(6) motion, claiming that the plaintiff has failed to state a claim upon which relief can be granted. This is the standard procedural mechanism for dismissing a case before discovery. It is particularly effective against self-represented litigants who fail to plead specific facts supporting each element of their legal claim. The court will accept the facts as true, but only if those facts are clear, relevant, and tied to the legal theory alleged.

Have I pleaded facts in enough detail to survive a motion to dismiss and justify access to discovery under Rule 26?

The motion to dismiss is almost always accompanied by a motion to stay discovery. This is a procedural chokehold. The Ninth Circuit has held that the purpose of Rule 12(b)(6) is to enable defendants to challenge the legal sufficiency of a complaint without subjecting themselves to discovery, and that a pending motion to dismiss is sufficient cause for granting a protective order. If granted, the stay prevents the plaintiff from requesting documents, taking depositions, or issuing interrogatories until the court rules on the motion to dismiss. If the dismissal is granted, discovery never opens. The result is that a plaintiff can lose entirely without seeing a single piece of evidence from the defendant.

This outcome is not rare. It is designed. The rules permit it, and courts prefer it. Discovery is expensive, disruptive, and risky for institutional defendants. Avoiding it is a strategic goal, and motions to stay serve that purpose well. Some jurisdictions apply automatic discovery stays during the pendency of motions to dismiss, treating them as tools of efficiency rather than opportunities for tactical suppression.

The plaintiff must respond with timing and precision. One effective tactic is to initiate the Rule 26(f) conference early, before the defendant files its motion to stay. This move triggers procedural obligations that can complicate the defense’s effort to halt discovery. The plaintiff can also oppose the stay by citing the risk of prejudice—arguing that delay prevents necessary fact development and unfairly advantages the defendant, who already possesses all relevant evidence.

If the court grants the stay, the plaintiff must prepare for a pure pleading contest. This shifts the burden entirely to the structure of the complaint. The plaintiff must anticipate the defendant’s interpretation of the law and plead facts that cannot be dismissed as implausible or irrelevant. This requires research, comparison with similar cases, and the ability to frame constitutional violations in terms that courts have previously recognized. It also requires avoiding surplus. Excessive detail, unrelated grievances, and emotional appeals weaken the pleading and give the court excuses to dismiss.

Post-Twombly and Iqbal, federal pleading standards require more than notice. The complaint must contain factual allegations that, if true, state a claim that is plausible on its face. Plausibility means the plaintiff has pleaded factual content that allows the court to draw the reasonable inference that the defendant is liable. This is not a probability standard, but it is more than possibility. Courts dismiss complaints that rely on threadbare recitals of legal elements, conclusory statements, or mere possibilities of misconduct. The plaintiff must plead facts, not legal theories, and those facts must create an inference of liability that is more than speculative.

Strip the Procedural Armor

Even when standing is met and the complaint survives dismissal, § 1983 plaintiffs face another procedural barrier: qualified immunity. Under Harlow v. Fitzgerald, government officials performing discretionary functions are shielded from liability unless their conduct violated clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known. This is a two-step inquiry: first, whether the facts alleged show a constitutional violation, and second, whether the right was clearly established at the time of the alleged violation.

If the defense moves to stay discovery, can I argue specific prejudice and procedural imbalance that favors immediate fact development?

The defense can raise qualified immunity at the motion to dismiss stage, and if successful, the plaintiff’s case ends before discovery. Courts analyze qualified immunity under the same pleading standards as Rule 12(b)(6), meaning the plaintiff must plead facts sufficient to show both a constitutional violation and a violation of clearly established law. This requires identifying case law that put the defendant on notice that the specific conduct at issue was unlawful. Abstract or general statements of constitutional rights are insufficient. The precedent must be controlling or clearly established to the point that every reasonable official would understand that what he is doing violates the right.

The burden of proof on qualified immunity is contested. Some circuits place the initial burden on the defendant to assert the defense, then shift the burden to the plaintiff to show a clearly established right. Other courts treat it as an affirmative defense with the burden remaining on the defendant throughout. Regardless of the allocation, the practical effect is the same: the plaintiff must plead facts and cite law that pierce the immunity shield, or the case is dismissed.

One narrow exception exists: extraordinary circumstances. If the official can prove that he neither knew nor should have known of the relevant legal standard, and his conduct was objectively reasonable, qualified immunity may apply even when the right was clearly established. Common examples include reliance on advice of counsel or reliance on state statutes later found unconstitutional. These exceptions are rarely granted, but they illustrate the depth of procedural protection afforded to government actors.

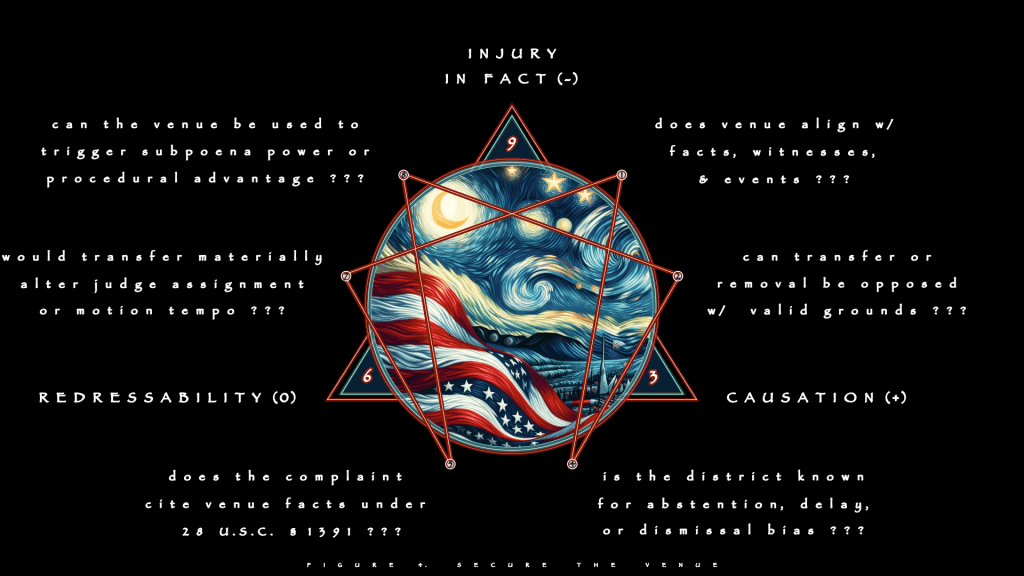

Control the Forum

Venue presents the third battleground. Unlike jurisdiction, which concerns the court’s power, venue concerns the location of the dispute. A § 1983 action may be filed in any district where the events occurred or where the defendants reside. However, this apparent flexibility creates exposure. If the venue is not anchored with factual clarity, the defense may file a motion to transfer under § 1404, citing convenience of witnesses, access to evidence, or docket efficiency.

Have I anchored venue with jurisdictional facts tying the harm, witnesses, and relevant events to the district I chose?

The defense does not request transfer arbitrarily. It requests transfer tactically. Certain districts are known for deference to governmental defendants, procedural hostility to pro se plaintiffs, or judicial calendars that stretch litigation over years. Moving the case into one of these forums can alter the balance of power substantially.

If the defense moves to transfer or remove the case, can I articulate—on record—why that shift would obstruct timely, just resolution?

To prevent transfer, the plaintiff must plead venue deliberately. This means including factual allegations that show the harm occurred in the district chosen, that key witnesses and evidence are located there, and that litigating elsewhere would increase costs or delay resolution. Courts give some deference to the plaintiff’s choice of forum, but that deference evaporates when the choice appears arbitrary or inconvenient.

In some instances, a plaintiff may prefer to remain in state court, believing that the local forum is more favorable. However, the defense can often remove the case to federal court under 28 U.S.C. § 1441. Once removed, the plaintiff cannot force the case back unless the court lacks subject matter jurisdiction. This removal power is another strategic tool used by the State. It shifts the procedural environment in ways that favor institutional defense.

Controlling venue, therefore, is not merely about location. It is about setting the procedural climate in which the case will unfold. Plaintiffs who understand this dynamic plead venue facts with care. They treat the initial filing not as a petition for fairness, but as the opening move in a positional game.

Procedural Fluency as Strategic Infrastructure

Together, standing, discovery access, and venue control determine whether a case is litigated on the merits or dismissed in the procedural shadows. These are not background issues. They are the procedural battlefield itself. Plaintiffs who master these elements do not guarantee victory, but they guarantee that the fight will happen.

Procedural fluency is not legal trivia. It is strategic infrastructure. Courts do not decide cases because they are important. They decide cases because the rules have been followed, the standards met, and the thresholds cleared. Any failure in that chain ends the litigation. The record will show no wrongdoing. It will show only “dismissed for lack of jurisdiction” or “failure to state a claim.”

A § 1983 action offers power, but only when wielded with precision. The statute creates liability for violations of constitutional rights by those acting under color of state law. That power is real, and it is feared by governments that know how discovery can expose pattern, motive, and misconduct. However, that fear is not activated by filings that fail the procedural tests. Only those complaints that pass through standing, survive dismissal, and retain control of venue ever reach the point where discovery becomes a threat.

Litigants who file with procedural blind spots are not underdogs. They are casualties. They arrive at court seeking redress and leave with rulings that do not address the harm at all. The law does not vindicate rights in the abstract. It enforces rights through rule-based systems that reward discipline.

Understanding this terrain transforms the role of the plaintiff. You are not asking the court to agree with you. You are building a path the court is permitted to walk. Every paragraph in your complaint is either a plank in that path or a hole through which your case will fall.

Mastering procedure does not eliminate risk. It does not overcome judicial bias, institutional inertia, or bad law. What it does is create pressure. That pressure compels the court to confront your claim on legal terms. It denies the defense the ability to escape through technicality. It keeps the fight alive.

If your case matters, it deserves that level of preparation, not because you want a fair fight—but because you want a fight at all.

Leave a comment