As the cursor blinks in the font menu, my legal brief honed, the choice between Times New Roman and Garamond is the final consideration. Far from a mundane choice, it catches like a thread on a nail. It begins not with curiosity but with capture, not with a decision to investigate but with the discovery that investigation is already underway. Those who have read Foucault’s Pendulum know the mechanism.

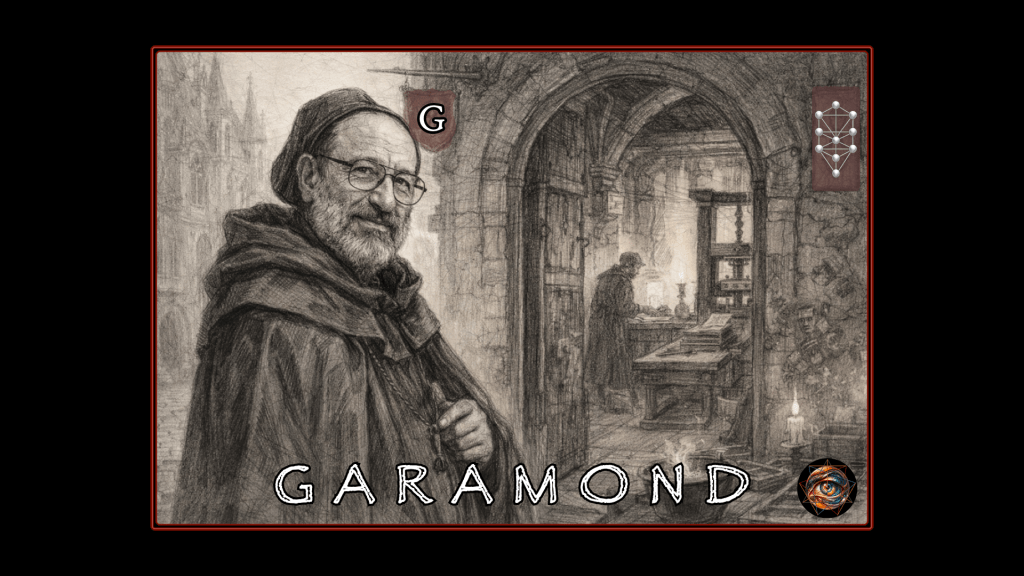

To the uninitiated, Garamond is simply a typeface, one of dozens in a dropdown menu, elegant and vaguely classical. For those who have spent too many nights with Umberto Eco, the name vibrates with accumulated strangeness. Eco buried a joke in his novel, a semiotic trap that never stops springing. To see “Garamond” in a font menu is to glimpse the Comte de St. Germain at a candlelit publishing party in Milan, is to hear vanity-press authors explaining their Templar theories to a man who believes nothing and collects payment for everything.

The thread pulls tighter. Tradition matters. The brief can wait.

A distinction hides beneath the familiar interface, one that most writers never consciously consider. Although digital culture has collapsed them into interchangeability, “font” and “typeface” are not synonyms. The latter is a design, an abstract architecture of letterforms existing nowhere and everywhere simultaneously. Garamond is a typeface. A font, historically, was a physical instantiation of that design: a specific size and weight of metal type cast from molten lead, stored in wooden cases, inked and pressed against paper by hand. The word descends from the Middle French fonte, meaning a casting or a melting.

To speak of a font was to speak of matter transformed by fire. This etymology carries an alchemical residue that Eco would have savored. The font was lead become language, base metal transmuted into the visible form of thought.

When Claude Garamond cut his punches in sixteenth-century Paris, he was engaged in a craft that Renaissance observers would not have sharply distinguished from other forms of hermetic making. The printing press was new and strange. The men who designed its letters were shaping the way thought itself would appear to the eye. Their work would outlast cathedrals.

The modern font menu performs a séance that passes unnoticed by nearly all its users.

The physical fonts are effectively gone, melted down centuries ago or rusting in museum drawers. What remains is pure form, mathematical descriptions of curves that once required steel and fire to produce. Every selection of “Garamond 12pt” invokes shapes whose material basis has vanished, ghosts summoned by software that knows nothing of their history. The word “font” persists as a fossil term, describing an object that no longer exists in the medium where the word appears. Those who notice the discrepancy have already begun to see too much.

Legal language operates through similar mechanisms of ghostly persistence. Words like “standing” and “relief” and “equity” carry the residue of physical acts, of bodies rising before tribunals, of hands extended in supplication, of scales that once existed as brass and chain.

The law, too, is a séance conducted in a specialized dialect. Those who learn to speak it discover that the words work even when no one remembers what they originally meant. This quality is shared by typography and jurisprudence alike. Both transmit authority from the dead to the living through forms whose origins have become invisible. To practice either craft is to become a medium, a channel for voices that stopped speaking centuries ago.

Umberto Eco intentionally named his cynical Milanese publisher Signor Garamond, and the joke operates on frequencies that reward obsessive attention. In Foucault’s Pendulum, Garamond runs two imprints from the same office. One publishes serious academic scholarship under respectable auspices. The other, a vanity press called Manutius, accepts payment from credulous authors eager to see their Templar genealogies and Rosicrucian fantasies rendered in type. The naming is precise: Aldus Manutius was the great Venetian printer of the Renaissance. Eco built a publishing house from the bones of typography’s patron saints, a mausoleum that accepts manuscripts.

Signor Garamond does not believe in the conspiracies he publishes. His genius lies in recognizing that belief is unnecessary for commerce. The hunger for hidden knowledge generates its own economy, and the publisher need only provide a service: transforming manuscript into book, suspicion into artifact, obsession into an object that can sit on a shelf and prove that someone, somewhere, took the author seriously. The typeface performs the essential labor. Nonsense set in Garamond is indistinguishable from genuine scholarship. The elegant serifs launder content, lending visual credibility to texts that might deserve none.

The punchcutter’s craft, perfected for prayer books and philosophical treatises, transmits paranoid fantasies with the same serene beauty it once lent to Erasmus. This is not corruption but the essential neutrality of form. A vessel does not interrogate what it carries. Claude Garamond designed letters; he did not design a filter for distinguishing truth from delusion. Signor Garamond understands this better than anyone in the novel, at least at first. The skeptic who profits from belief is safer than the skeptic who plays with it.

Safety is not the same as innocence, however, and the publisher’s hands are not clean merely because the ink is dry.

History, or legend, records the Comte de St. Germain as an eighteenth-century courtier of uncertain origin who appeared at Versailles, at the salon of Madame de Pompadour, at a dozen glittering courts, always immaculately dressed, never aging, never quite confirming or denying the miraculous rumors that preceded him. He claimed to possess the Philosopher’s Stone. He claimed fluency in every language. He hinted at memories stretching back centuries, at dinners with the Queen of Sheba, at secrets too dangerous to speak directly. Voltaire called him “the man who never dies and who knows everything.”

The Count sold access to mysteries he may or may not have possessed, and his commercial method deserves admiration for its elegance. He required no laboratory, no library, no apparatus of proof. His product was himself: his presence, his manner, his imperturbable air of knowing more than he would say. Patrons paid for proximity to the enigma. Whether or not the Philosopher’s Stone exists mattered less than whether the Count seemed like a man who might possess it. Appearance performed the work of substance. The performance of esoteric knowledge, especially before the uninitiated, often passes for the genuine article.

St. Germain died in 1784 … or not. Sightings continued for decades. Theosophists canonized him as an Ascended Master, still walking among the living, still guarding the ancient wisdom. The uncertainty was always the point. An immortal who could be definitively verified would become a specimen, a curiosity for natural philosophers and medical examiners. An immortal who might be a charlatan retains his power precisely because the question never closes. Signor Garamond operates by the same principle. He publishes books that might contain hidden truths. He does not endorse them. He does not refute them. He collects payment and allows the mystery to compound interest.

The typeface completes the trinity.

Claude Garamond died in 1561, yet his shapes continue to appear on screens and pages five centuries later, carrying arguments he never imagined into futures he could not have conceived. The punchcutter achieved what the Count only claimed: actual immortality, persistence through form rather than flesh. Every brief set in Garamond, every dissertation, every conspiracy tract, receives the touch of hands that stopped moving before Shakespeare was born. The appearance of authority is authority itself. The dead man’s aesthetic judgments still determine whether a reader trusts a text, still whisper credibility into documents whose contents he would not have recognized, still perform their silent work of persuasion in languages he never spoke.

Jacopo Belbo, the tragic center of Eco’s novel, understands that the Plan he helps construct is a parody. He and his colleagues assemble their grand conspiracy from index cards and drinking games, mocking the very manuscripts that Signor Garamond publishes for profit. They know the Templars did not possess a secret that has shaped all of Western history. They know the connections they draw are arbitrary, a demonstration of how pattern-hungry minds manufacture significance from noise. The Plan is a joke, a scholarly prank, an elaborate game among educated cynics who consider themselves immune to the credulity they satirize.

The horror of the novel is that the joke becomes real, not because the conspiracy was true all along, but because belief does not require truth to produce consequences.

Belbo builds a labyrinth for amusement and then cannot find the exit. The true believers, the Diabolicals who have spent their lives searching for the secret, discover the Plan and assume it must be genuine. No one would construct something so elaborate as a mere parody. The sophistication of the fabrication becomes evidence of its authenticity. Belbo dies for a secret he invented, hanged by men who refuse to accept that the treasure map leads nowhere.

Eco’s warning operates on levels that the cleverest readers do not escape. The novel is itself a trap, a demonstration of seductive pattern-making so elaborate that readers have been known to investigate its fictional sources as though they were historical documents. Signor Garamond’s vanity-press customers find their mirror in the reader who cannot quite believe that a scholar of Eco’s stature would fabricate historical references, who searches for the genuine Plan behind the fictional one, who becomes, in the act of investigating, another customer for mysteries that do not exist. The novel vaccinates and infects simultaneously. It immunizes the reader against taking conspiracies seriously while rendering the reader incapable of ignoring them entirely. Every Templar reference encountered afterward arrives pre-annotated, trailing the echo of Belbo’s laughter turning to terror.

Irony provides no immunity. This is the sentence that should appear above every library door, embroidered on every graduate student’s pillow. Knowing the game is a game does not prevent the game from capturing you. Belbo knew. The knowledge did not save him. Knowledge is NOT power. The thread snagged, he followed it and the labyrinth closed behind him. Readers of his story undergo a lesser version of the same capture. We cannot unread the patterns that have become permanent overlays on our perception. We are altered without consent. This is the price of admission. The ticket cannot be refunded.

The dropdown menu is not neutral territory. The name “Garamond” pulses with accumulated strangeness, trailing ghosts of a sixteenth-century punchcutter, an immortal count, a cynical Milanese publisher, a fictional editor who died for a fabrication. There is more to the mechanism than metaphor. Perception genuinely changes when patterns are installed. To notice is to be conscripted. The font menu, once a utilitarian grid of aesthetic choices, is become a cabinet of whispers, a séance waiting to be begin.

Leave a comment