The circulating RICO narrative may be more political technology than prosecutorial reality, but the distinction matters less than critics assume. Democrats built something over the past few decades that functions beautifully as a political machine and terribly as a defensible position. The word “enterprise” doesn’t need a conviction to leave a mark.

Somewhere in the apparatus of the second Trump administration, someone is reportedly thinking about RICO. Not as a case filed, not as an indictment sealed, but as a concept, a shape, a way of looking at the opposition that reframes political competition as criminal prosecution. George Papadopoulos says a grand jury was empaneled in Florida. Treasury Secretary Bessent mentions “disturbing tapes” from Minnesota and promises that “when the bear trap snaps, we’re going to get these folks.” The President himself promises “reckoning and retribution.” Whether any of this amounts to a coordinated legal strategy or merely a coordinated messaging strategy is, for the moment, unknowable.

What is knowable is the logic. If you wanted to prosecute Democratic institutional actors at scale, how would you go about it? Where would you apply pressure? What would distinguish a serious campaign from performative noise? These questions matter regardless of whether the current chatter reflects operational reality or aspirational theater.

The Prosecution-Shaped Ecosystem

The Democratic Party is not a mafia. It is something more modern and, in certain respects, more exposed: a networked ecosystem of foundations, nonprofits, advocacy organizations, donor pipelines, consultant shops, and revolving-door professionals who move between government, civil society, and campaign work with the ease of diplomats changing embassies. Nobody commands this system because nobody needs to; shared ideology functions as coordination protocol. While the hymns change seasonally, the choreography persists.

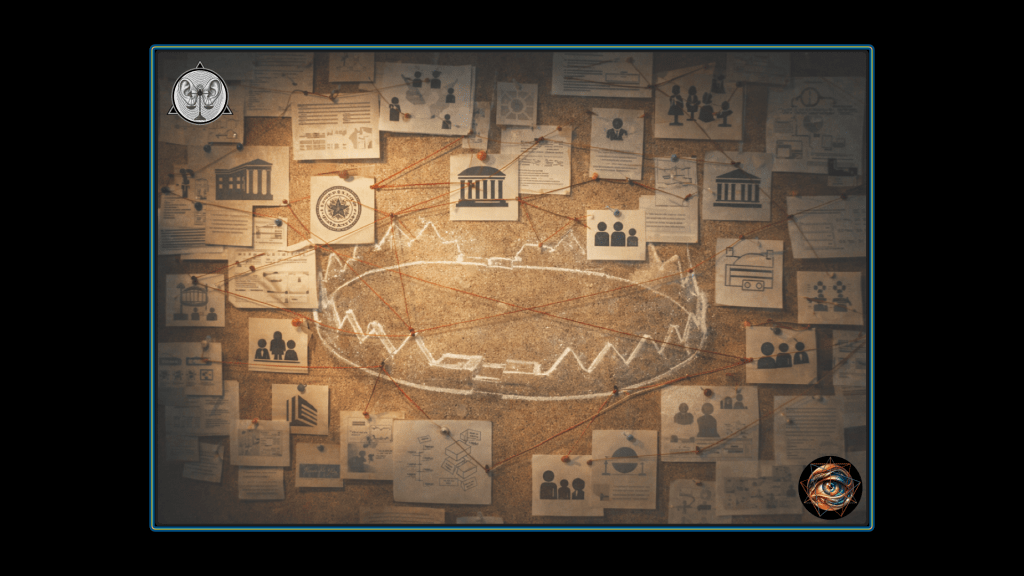

This architecture is legal, common, and effective at mobilizing resources. It is also visually indistinguishable from what federal prosecutors call “an enterprise.” RICO does not require a mastermind issuing orders from a secure compound. It requires a pattern of activity, a set of relationships, and predicate offenses that can be narrated as connected. The question is never “did someone explicitly coordinate these activities?” It is enough to ask, “can a prosecutor tell a story in which these activities appear coordinated?” Democrats, by building politics into an interdependent economy, keep producing diagrams that look like exhibits in a racketeering seminar.

The vulnerability is structural, not moral. You can be entirely innocent of criminal intent and still find yourself standing in a formation that resembles guilt. The ecosystem’s great strength, its ability to move resources and influence without explicit command, becomes its weakness when an adversary decides to redescribe that fluidity as conspiracy.

The Powell Precedent

Skeptics of the RICO narrative have a strong default objection: this is just talk, red meat for the base, the kind of promise that dies quietly when it meets the evidentiary standards of federal court. The objection is reasonable. Political movements routinely promise prosecutions they cannot deliver.

The Powell investigation, however, complicates this dismissal. For two months, the Department of Justice ran a criminal investigation into the sitting Chairman of the Federal Reserve without a single leak—no whistleblowers, no anonymous sources, no advance warning. The investigation became public only because Powell himself disclosed it on January 11, 2026. Until that moment, the consensus assumption was that no such investigation existed.

This does not prove that a sprawling RICO case against Democratic institutions is underway. Rather, it proves something narrower and more unsettling: that the current DOJ can maintain operational security on sensitive investigations involving high-profile targets. The absence of public evidence is no longer reliable evidence of absence. The Powell precedent does not confirm the bear trap exists. It confirms that a bear trap could exist without anyone outside the trapping party knowing until it snaps.

Minnesota as Proving Ground

If you were looking for a jurisdiction to test the enterprise theory, Minnesota would present itself like an unlocked door. The numbers are real: federal prosecutors estimate over nine billion dollars in fraudulent claims across multiple welfare programs. The convictions are real: ninety-two individuals charged, sixty-two convicted, schemes spanning childcare subsidies, meal programs, and autism therapy services. The political proximity is real. Elected officials including the governor, the attorney general, and at least one congresswoman have documented relationships with individuals now imprisoned for fraud.

What remains contested is the nature of that proximity.

Were these politicians “merely complicit,” as one commentator put it, or “part of a broader conspiracy”? The audio recording of Attorney General Keith Ellison meeting with individuals later convicted exists. The characterization of that meeting as evidence of corruption does not, at least not yet. Treasury Secretary Bessent referenced the tapes while deploying the word “allegedly” with the caution of a man whose lawyers were standing just off-camera.

The strategic value of Minnesota is not that it proves high-level Democratic criminality. It merely provides a laboratory where financial crimes are documented, investigative infrastructure is in place, and the distance between convicted fraudsters and elected officials can be measured without a telescope. A serious prosecutor would not need to prove that Tim Walz personally stole money, only to establish that his administration created conditions in which fraud flourished, that warnings were ignored, that oversight was actively resisted. The predicate offenses write themselves: wire fraud, false statements, conspiracy to defraud the United States. The standard is not “smoking gun.” The standard is “pattern of conduct consistent with facilitation.”

Whether that standard can be met is a question for grand juries. That someone is asking the question is no longer in doubt.

The Donor Squeeze

Elected officials make satisfying headlines, but they are not the pressure point that matters most. The real leverage in any RICO-style campaign lies one layer back: the mega-donors, bundlers, foundation executives, nonprofit boards, and professional intermediaries who constitute the financial and institutional spine of Democratic politics.

These people are not built for combat. They entered political philanthropy expecting influence and dinner invitations, not subpoenas and depositions. The mere prospect of becoming a “person of interest” in an enterprise investigation introduces friction into relationships that depend on smoothness. Lawyers must be consulted. Board meetings grow tense. Grant-making slows while compliance reviews multiply. The ecosystem runs on lubrication; introduce sand and the gears begin to grind.

This is why RICO functions as political technology even in the absence of convictions. One need not prosecute the Democratic Party to damage it, only to make participation in Democratic institutional life feel expensive and exposed. The threat of investigation travels faster than investigation itself. Donors compare notes with donors. Foundations consult their insurers. Consultants update their risk assessments. By the time any case reaches trial, years of institutional disruption have already occurred.

The sophistication of this approach lies in its asymmetry. Elected officials can absorb legal threats as badges of honor; their base rallies around persecution narratives. Administrators and benefactors enjoy no such luxury. They operate in a world where reputation is currency and ambiguity is poison. An investigation that never results in charges can still produce resignations, reduced giving, and the quiet contraction of an infrastructure that took decades to build.

The Rhetoric Comes Home

There is a karmic dimension to the current moment that will not be acknowledged at Democratic fundraisers. For years, the party’s dominant rhetorical mode treated political opposition not as disagreement but as danger. Threats to democracy, enemies of the people, disinformation as violence, dissent as sabotage: the vocabulary of emergency became the vocabulary of ordinary competition. Institutions were weaponized while being proclaimed neutral. Lawfare was normalized as method while being denied as concept.

This framing was effective. It mobilized voters, justified aggressive action, and positioned Democrats as defenders of civilizational order against barbarism. It also taught the public to understand politics as a criminal drama, a story in which one side represents legitimate governance and the other represents existential threat.

The difficulty with teaching this lesson is that students eventually apply it in contexts the teacher did not intend. When Republicans reach for RICO language, when they describe Democratic institutions as an “enterprise” engaged in “conspiracy,” they are speaking a dialect that Democrats themselves popularized. The emotional register is identical; only the target has changed. When you train a population to see politics as crime, you cannot control which defendants the jury eventually selects.

The Weapon on the Wall

The uncomfortable conclusion is not that Democrats are guilty, but that guilt is beside the point. The RICO narrative functions as a weapon through deployment, not verdict. Its power lies in the word “enterprise,” a term that sticks to institutional skin like tar and requires no conviction to inflict reputational damage. You can lose every case and still win the war if you have succeeded in recoding “opposition” as “organization.”

Democrats are particularly vulnerable to this attack because their self-conception depends on institutional legitimacy. Their brand is competence, expertise, the responsible stewardship of complex systems. When someone labels that stewardship a “criminal conspiracy,” they are not merely making an accusation; they are vandalizing the altar on which Democratic identity rests.

Whether the current RICO chatter represents a serious prosecutorial strategy or merely the ambient noise of a political movement entertaining its base remains uncertain. The Mueller investigation was real; the Durham investigation was real; the capacity of the federal government to investigate its adversaries is not in doubt. What remains unknown is intention, competence, and the gap between what partisans promise and what prosecutors can prove.

The motive is legible. The target is defined. The vulnerabilities are structural. Somewhere in the apparatus, someone is drawing diagrams.

Leave a comment