In the age of sail, frigates did not defeat ships of the line through direct engagement. The mathematics were impossible: a thirty-two-gun frigate could not stand against a seventy-four-gun battleship in a broadside exchange. A battleship’s oak walls were three feet thick. The gun deck carried carronades that could dismast a frigate with a single salvo. Yet frigates won wars. The frigate captain who understood his position did not seek the decisive battle. Rather, he harassed supply lines, captured merchantmen, gathered intelligence, and forced the enemy fleet to disperse its strength chasing shadows across the Atlantic.

Sly strategist that he was, he accumulated small victories that shifted the larger balance without ever risking annihilation.

The Pro Se Litigator faces similar asymmetry. The institution commands more resources, more experience, and more credibility with the court. The courthouse architecture itself palpably communicates the disparity. Fluorescent lights hum above rows of plastic chairs as the bailiff’s studied indifference looks past the clerk’s desk stacked with forty case files that reduce any given matter to one manila folder among many. Direct confrontation on the institution’s terms is a losing proposition. Yet he, too, can prevail, not by overpowering the opposition but by craft and by maneuver. He may decide when and where to engage, and make every filing count toward a cumulative effect that the institution cannot easily counter.

Motion practice is the frigate’s art: inferior firepower deployed with superior positioning.

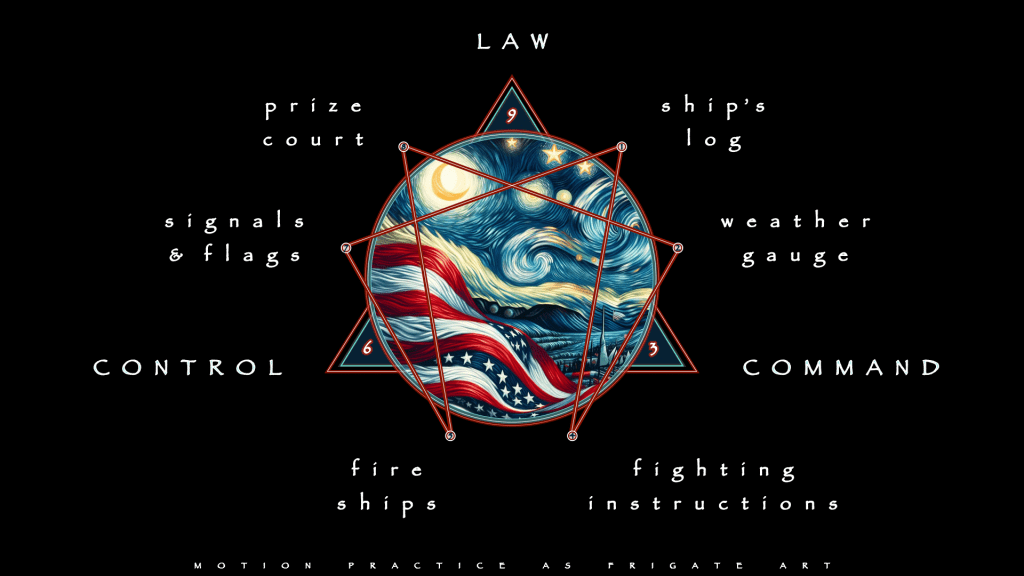

What follows is a primer drawn from Napoleonic naval warfare. The Six Correspondences are not decorative, despite their beauty. Each maps onto a specific behavior. The Pro Se Litigator fluent in these does not thereby become a captain. Mastery of that kind requires years of practice under fire. These principles provide the missing comprehension that separates crewmen from cargo. Cargo is carried. Crewmen participate. At first, the difference is in understanding why the ship turns when it does. Later, the practice becomes the art of knowing how.

Ship’s Log

The Battle Occurs In The Permanent Record, Not The Ephemeral Courtroom

Every naval vessel kept a log, a leather-bound ledger filled daily in the captain’s own hand or that of his clerk. Though the pages yellowed in the salt air and the ink feathered in humidity, the entries accumulated in a cadence as regular as the watch bells. “At four bells of the forenoon watch, sighted sail bearing northeast by east. Cleared for action. At six bells, recognized chase as French merchantman. Fired warning shot across bow. Prize crew away at seven bells.” The log was not merely administrative. It was the legal artifact to be consulted in courts-martial, prize adjudications, and Admiralty inquests years after the voyage ended.

What was not in the log did not officially happen; whatever was therein could not be unsaid.

The case docket is the ship’s log of litigation. Every filing, every order, every transcript entry becomes part of a permanent record that will outlive the hearing, the judge, and perhaps the litigants themselves. The fiction of live courtroom dialogue is that it carries legal weight. In reality, if something is not in the record, it did not happen. The judge may redden with irritation, the opposing counsel may roll their eyes, the courtroom may feel saturated with unspoken hostility. None of it survives. Only the filings survive. The record has no tone of voice. It cannot be intimidated, charmed, or worn down. It simply persists.

Most litigants enter court believing the judge is the audience. This is a category error. The real audience is threefold: the appellate panel that may one day review the record, the public archive to which every filing contributes, and the opponent whose future posture depends on contradictions they cannot later escape. The motion is not a plea to the judge. It is an entry in the log, written for readers who have not yet arrived.

The Pro Se Litigator who understands this writes differently: every sentence composed as though a stranger will read it in five years and judge its author by its precision.

Weather Gauge

Initiative Decides Who Frames The Dispute

Before modern engines, the ship that held the weather gauge held the windward position relative to the enemy. This conferred a decisive advantage: the windward ship chose when to engage, at what distance, and on what terms. Her crew worked the guns on a level deck while the leeward ship heeled away from them, her gunners firing uphill, her lower ports closed against the sea that sloshed through the scuppers. The windward captain could close to pistol range or stand off and punish with long guns; the leeward captain could only receive what was given. A captain who surrendered the weather gauge surrendered initiative; he would fight when and where his opponent chose, on a tilted deck, half-blinded by spray.

Filing initiative is the weather gauge of litigation. The Pro Se Litigator who files first on an issue frames the terms of the dispute. The opposition must respond to that characterization of facts, that selection of legal standards, that construction of the narrative. They are fighting upwind, reacting to a position rather than establishing their own. Surrendering the weather gauge means waiting for the opponent to file, then scrambling to reframe what they have already defined. By then the court has read their version first.

Any response arrives as correction rather than as truth.

Most attorneys file defensively, responding to motions rather than initiating them. This is the leeward posture: safe, conventional, and perpetually reactive. The strategic litigant files offensively, seizing the weather gauge whenever procedural rules permit. A motion filed before the opponent expects it, addressing an issue they assumed would remain dormant, forces them into defensive maneuvering. They must respond on an imposed timeline, in an imposed frame, on an imposed battleground. Initiative is not aggression; it is positioning. The ship that holds the weather gauge need not fire a single shot to control the engagement. The opponent knows, and the knowledge constrains everything they do.

Fighting Instructions

The Reactionary Gap Between Rules and Convention Is Tactical Room To Maneuver

The Royal Navy of the eighteenth century operated under the Fighting Instructions, a codified tactical doctrine that prescribed how engagements should be conducted. Ships were to form a line of battle, engage their opposite number, and maintain formation at all costs. The Instructions were designed to prevent chaos, but they also prevented initiative. Admiral John Byng learned this at the cost of his life: at the Battle of Minorca in 1756, he followed doctrine rather than pressing an attack against a retreating French fleet. He was court-martialed, convicted of failing to do his utmost, and shot by firing squad on the quarterdeck of HMS Monarch. Voltaire’s acid summary endures: the English shot their admiral “pour encourager les autres.” The Fighting Instructions demanded conformity; deviation meant death, even when deviation would have meant victory.

Then came commanders like Nelson, who understood that the Fighting Instructions were not the law of the sea but merely the convention of the service. The rules permitted maneuvers that doctrine discouraged. At Trafalgar, Nelson broke the line in two columns, divided the Combined Fleet, and achieved decisive victory by doing what his opponents assumed no British admiral would dare. He exploited the gap between what was allowed and what was expected. The French and Spanish captains, trained in the same doctrine, could not adapt quickly enough to a battle that refused to follow the script.

Legal procedure has its own Fighting Instructions: the filing schedules, motion formats, and argumentative postures that have hardened into convention through repetition.

Most attorneys follow these conventions because deviation feels risky, because the bar taught conformity, because judges expect predictability. The Pro Se Litigator who studies the actual rules discovers room to maneuver that convention has obscured. A motion filed in an unexpected form, at an unexpected time, addressing an unexpected issue, can disrupt the opponent’s assumptions more effectively than a conventional motion with superior arguments. The institution expects conformity. When it does not arrive, the institution must adapt, and adaptation under pressure produces errors. No one will be shot for breaking formation.

Opponents might, however, lose their balance.

Fire Ships

Force Response; Extract Documentation; Lure Institutions To Leave Fingerprints

The fire ship was a sacrificial weapon, a vessel already condemned. Her crew would load her hold with tar, pitch, faggots of dry wood, and hemp rope soaked in turpentine. They would sail her toward the enemy fleet at night, skeleton crew at the helm, timing their escape to the last possible moment. At the right distance they would light the fuses, leap into a trailing longboat, and row hard for safety while flames climbed the ratlines behind them. At the Battle of the Basque Roads in 1809, Lord Cochrane sent fire ships and explosion vessels against the French fleet anchored in the Aix Roads. The French captains panicked, cut their anchor cables, and ran aground in the darkness. Only four French ships remained in navigable water by morning. The fire ships themselves destroyed almost nothing directly; their value was in the chaos they provoked, the documentation they forced, the courts-martial that followed for French officers who had abandoned their posts.

Some motions are fire ships. They are filed not to win but to force the opponent into costly defensive maneuvers. A motion that raises an uncomfortable issue, even if certain to be denied, requires the opponent to respond on the record. A motion that exposes a procedural irregularity, even if the court excuses it, forces the judge to go on record with the excuse. The denial is not the failure, but the detonation.

What matters is what the fire ship forces into the open.

Too many Pro Se Litigators equate success with a motion being granted. This metric misunderstands the game. A denied motion still obliges the court to articulate a reason, and that reason becomes part of the log. A denial that forces an absurd rationale is more useful than a granted motion that concedes nothing. The fire ship motion is a provocation designed to extract response. It does not ask for relief; it forces documentation. The opponent’s evasion, the judge’s contortion, the institution’s fingerprints on its own failures: these are the fires that spread after the ship has burned. The French captains at Basque Roads were not destroyed by flame. They were destroyed by what the flame made them do.

Signals and Flags

Verbosity Is Noise; Precision Is Signal

Naval communication in the Early Modern era depended on signal flags, a constrained vocabulary of colored pennants that could be read across miles of ocean. The signal book contained hundreds of predefined messages, but no provision for nuance. Captain Home Popham’s Telegraphic Signals of 1800 expanded the vocabulary, yet even Popham’s system had limits. At Trafalgar, Nelson wished to signal “England confides that every man will do his duty,” but “confides” was not in the book; it would have to be spelled letter by letter, costing time the fleet did not have. The signal that flew instead used “expects,” which was in the vocabulary. The message that reached the fleet was not quite what Nelson intended, but it was clear. Clarity was survival. A misread signal could send a ship in the wrong direction, expose a flank, lose an engagement. The flag that flew was the only message that existed.

Motion drafting is signaling under constraint.

The court, like a distant ship, reads only what is flagged clearly. Verbosity is noise; precision is signal. A motion that buries its point in qualifications, digressions, and anticipatory rebuttals has hoisted too many flags at once; the message is lost in the clutter. A motion that states its request in a single clear sentence, supported by facts the court can verify and law the court must apply, has signaled effectively. The court may deny the motion, but the court will have understood what it denied, and the denial will be specific enough to matter on appeal.

Most litigants write as though more words meant more persuasion. The opposite is true. Every unnecessary sentence dilutes the signal. Every elaboration beyond what the argument requires provides material for the opponent to mischaracterize. The disciplined motion contains exactly what it needs and nothing more: the request, the factual basis, the legal authority, the conclusion. Strip the rigging to fighting sail. Signal what matters. Let the flags speak without amplification. Nelson could not send “confides.” He sent what the system allowed, what the fleet understood … nothing missing, nothing extra.

The Prize Court

The Appellate Panel Will See Only What Was Written

There was more to Napoleonic naval warfare than sinking enemy ships. The highest ideal was to capture them as prizes. Such a vessel became property to be adjudicated in prize court, an oak-paneled chamber in Plymouth or Kingston or Antigua where clerks turned pages of depositions and judges examined ships’ logs under gray maritime light. The legality of the capture, the distribution of prize money, the conduct of the engagement: all of it was reviewed based on documentary evidence. The captain who fought brilliantly but documented poorly might win the battle and lose the prize. There are records of officers denied their share because the log did not adequately establish that the captured vessel was lawful prize, or because signals were not properly noted, or because the sequence of events could not be reconstructed from what was written. What mattered in the prize court was not what happened but what the log recorded, what the signals showed, what the witnesses could swear to from written orders.

The appellate court is the prize court of litigation.

The trial is the engagement; the appeal is the adjudication. What matters on appeal is not what happened in the courtroom but what the record contains. The judge’s tone, the opponent’s visible discomfort, eloquent oral argument: none of it survives. Only the filings survive. The transcripts survive. The orders survive. The appellate judges were not there; they know only what the paper tells them. A brilliant argument that was not preserved by objection does not exist for appellate purposes. A devastating admission that was not captured in the transcript cannot be cited.

This is why the log matters, why the weather gauge matters, why signals must be clear and fire ships must force documentation. The prize court is always watching, even when the battle feels immediate and local. The Pro Se Litigator who understands this fights differently: not to impress the trial judge but to construct a record that will speak for itself when reviewed by strangers. The captain who lost his prize money in Plymouth because his log was incomplete learned a lesson that cost him years of income. The lesson was not one of seamanship, but documentation. The prize court sees only what was written.

Write accordingly.

Able Seaman

Although the Six Correspondences are mapped and circumnavigated, one thought-provoking essay does not a captain make. Only years at sea can do that. What this essay can do is move you from passenger to crew, from incomprehension to orientation. The cargo below decks experiences the voyage as a series of unexplained lurches, delivered finally to a destination it did not choose. The crew lives in the weather, hands on the lines, feet braced against the pitch and roll, understanding why the helm goes over before the order is spoken.

The Pro Se Litigator who remains cargo will be carried through the legal process by forces that remain invisible, deposited at a judgment shaped entirely by others. He who becomes crew still faces the same winds, the same procedural seas, the same institutional fleet bearing down with superior firepower. The difference is comprehension: knowing why the maneuvers are executed, anticipating what comes next, recognizing the tactics as they unfold.

The next motion filed under these principles will not win a case by itself. What it can do is enter the log in chosen terms, seize or maintain the weather gauge, and exploit the gap between rules and convention. No single broadside wins a naval campaign. It can, however, force a response that documents what would otherwise remain hidden, signal clearly to a court that reads only what is flagged, and build a record that will speak in the prize court that one day may convene.

The difference between cargo and crew is not talent, or resources. The decision to learn how the ship moves and why is only the beginning. That knowledge is available to anyone who seeks it, but knowledge is not power. The seeking is work. Work is the point.

Leave a comment